BBC Music Magazine recently posted a list of “Forgotten Piano Concertos”, and most of them are news to me. But I want to supplement the list with some concertos by American composers that very much deserve greater attention.

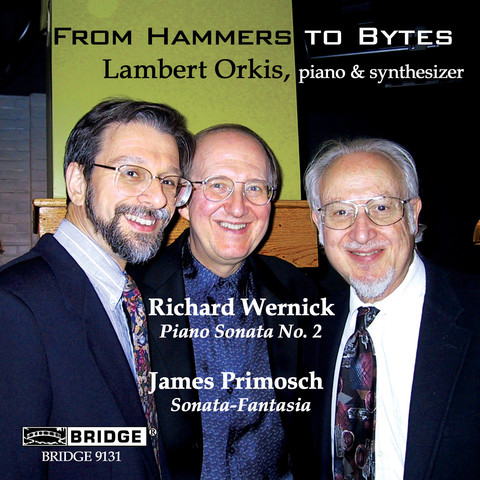

Richard Wernick’s Piano Concerto was written for Lambert Orkis and recorded for Bridge with the composer conducting Symphony II, an ensemble originated by musicians from the Lyric Opera of Chicago’s orchestra. There are exceedingly few American composers who are not underappreciated, but Wernick’s tautly constructed and passionately heartfelt music truly should be more widely recognized. Lambert Orkis is best known as a superb chamber musician, but acquits himself brilliantly as a concerto soloist, and Symphony II is highly impressive. The piece is not on YouTube, but the following offers a sample of a recent Wernick chamber work.

Richard Goode is one of our most distinguished pianists in the standard repertoire, but earlier in his career he played and recorded several pieces by the late George Perle, including his Concertino for Piano, Winds and Timpani, and the Serenade Nr. 3 for piano and orchestra. Along with Perle’s solo Ballade, these pieces were recorded by Goode for Nonesuch, with Gerard Schwarz conducting his Music Today Ensemble. That album is available through Arkiv Music, but the Serenade performance was re-issued on a two-disc Bridge compendium of Perle’s music, along with a recording of the Concerto No. 2 with Michael Boriskin and the Utah Symphony under Joseph Silverstein that was originally released on Harmonia Mundi. Perle was a leading music theorist, explicating a variety of 20th century musics, with special emphasis on the Second Viennese School, but he should be no less renowned for his compositions. His piano writing is always attractive, with plenty of lyricism, but, most characteristically, fleet toccata-like textures. (Previously I wrote about Perle’ piano music here.) I nominate the Serenade No. 3 for revival. Here is the first movement:

Melinda Wagner’s Extremity of Sky is a piano concerto that was written for Emmanuel Ax. This is a grandly-scaled four-movement work by a master of the orchestral medium. The piano writing is no less eloquent, idiomatic but fresh, and harmonically rich, with perhaps some Messiaen influence. The slow movement, contemplative and dramatic by turns, is deeply touching. The piece is not yet commercially recorded, but as an example of her music, here is the opening movement of her Trombone Concerto:

Pianist Robert Miller died much too young, cutting short a career devoted to new music of many varieties, from Babbitt to Crumb, and including a 1978 Piano Concerto by the then 40-year old John Harbison. The piece was recorded for CRI with Miller, and the American Composers Orchestra, with Gunther Schuller conducting. Re-issued on CD by CRI as part of a disc of several early Harbison pieces, the album is now available through New World Records. Harbison’s concerto is one of the pieces that marked his turn toward a more direct and open idiom, sometimes characterized as neo-romantic, though jazz, Bach, and Stravinsky are perhaps more fundamental to his musical interests. The Concerto is not on YouTube, but as a sample of his orchestral writing, here is a later work, the Symphony No. 2.

I could continue this list for a while, with pieces by Peter Lieberson and Christopher Rouse among many others. Suggestions in the comments for additional pieces are, of course, welcome.